By Frank McDonald. Originally published in The Ditch's State Failures.

Leo Varadkar, Simon Coveney, Eoghan Murphy and Paul Hyde have at least one thing in common: they all played crucial roles in implementing a classically neoliberal thesis that solutions to Ireland’s housing emergency would be found by relying on – and directly facilitating – the market. And the general public needs to much better understand how that happened.

Michael Noonan laid the groundwork in Section 41 of the 2013 Finance Act, which exempted real estate investment trusts from paying corporation tax on their rental income from Irish commercial and residential property or capital gains tax on the disposal of such assets. Thus the stage was set for institutional funds, mainly from abroad, to become the principal source of financing for property development in Ireland.

If this wall of money was to be captured, our planning process – considered by investors as cumbersome – would need to be streamlined, according to a narrative spun by Property Industry Ireland (PII). A division of IBEC, PII was set up in 2011 to forge an alliance of private sector professionals: architects, chartered surveyors, structural engineers, developers, planning consultants, bankers, asset managers, estate agents and others.

PII describes itself as “the most influential property group in Ireland”. Many of its activists honed their networking skills during the post-crash recession attending lectures by thought leaders hosted by the Urban Land Institute’s Irish branch or getting involved in the Academy of Urbanism. A consensus emerged that what Ireland needed was a neoliberal, deregulated planning system, and they set about working to achieve this goal.

No lobbying of government by vested interests has been so well-documented as the intensive multi-pronged campaign of persuasion coordinated by PII to change the planning laws in 2016 – and this has continued relentlessly ever since. It was (and still is) carried out by a new breed of lobbyists who can more accurately be described as policy entrepreneurs. They effectively succeeded in capturing public policy on housing.

Published by the European Planning Studies journal in 2019, De-democratising the Irish Planning System – a peer-reviewed academic paper by postgraduates Mick Lennon of UCD and Richard Waldron of Queen’s University Belfast – documented what went on by conducting off-the-record interviews with key participants, including politicians, civil servants, developers, planning consultants and lobbyists.

“Opposition to the right of third-party appeals on planning applications was a frequently recurring theme with the question posed as to ‘why does Joe Public have the same right as the developer every time’,” as one interviewee said, adding that this was “democracy gone a bit too far”. And with the appointment in 2016 of a new housing minister in Simon Coveney, PII saw an opportunity to change the planning system.

With Fine Gael in government there was “a politically receptive environment” for these ends, as Lennon and Waldron wrote.

As luck would have it

In pushing for a policy shift, “PII drew on its extensive membership to propagate a broad discourse coalition comprising actors from across the development sector. This process was facilitated by the dual membership of many PII members either of other lobby groups such as the Construction Industry Federation and the Urban Land Institute, or of professional bodies, such as the Society of Chartered Surveyors of Ireland.

“This broad coalition of members aligned to a single storyline of cause and effect provided PII with a ‘claims to a hearing’… as an organisation legitimately representing the voice of the development sector. Complementing this were various longstanding professional and personal relationships among the extensive membership of PII that were drawn on by the PII council to facilitate ‘access’ to pertinent civil servants and politicians.”

As luck would have it, in May 2016, Cork-born developer Michael O’Flynn – a PII council member – did an interview on RTÉ radio with the late Marian Finucane, floating the radical idea that all planning applications for 100-plus houses or apartments and 200-plus student bed-spaces should go directly to An Bord Pleanála, bypassing the local authorities. Coveney heard it, rang him up and invited a PII delegation to meet him.

One of the participants – known to be a leading private sector planning consultant – later told Lennon and Waldron, “We met him four times over about six or seven weeks for, amazing actually, from eight o’clock at night until midnight. And he went through what his vision was for the Irish planning property system. And we gave him our recommendations and they took it lock, stock and barrel and stuck it into the new Housing Bill.”

Thus the 2016 Planning and Development (Housing) and Residential Tenancies Act turned An Bord Pleanála into a “one-stop shop” for large-scale housing schemes, bringing its staff into direct contact with developers and their teams of consultants for the first time since it was established in 1977. Nobody foresaw the dangers that this would pose for the board’s independence and its reputation for impartiality.

Coveney’s headline initiative was an “action plan for housing and homelessness” grandly titled Rebuilding Ireland, which set a target of 25,000 new homes per annum over a five-year period. However as Maynooth University’s Dr Rory Hearne pointed out at the time, one of its major flaws was that “it accepts that a majority of new households will not be able to own their own home” and would have to resort to renting instead.

But Coveney didn’t last long. After Leo Varadkar defeated him in the contest to succeed Enda Kenny as leader of Fine Gael, he moved from the Custom House to Iveagh House in June 2017 to become foreign affairs minister. Varadkar then appointed Dubliner Eoghan Murphy as housing minister. The property lobby couldn’t have been more pleased. They knew he would deliver.

Murphy lost no time in drafting new mandatory ministerial planning guidelines that were deliberately tailored for the build-to-rent (BTR) sector, whittling down the size and mix of apartments in exclusively BTR developments and introducing co-living schemes – with room sizes as low as 12 square metres, the same floor area as a standard car parking space – which he ludicrously likened to “very trendy boutique hotels”.

Ostensibly justified on the basis that more singles needed to be catered for in the context of having “a young and increasingly internationally mobile workforce”, Murphy’s 2018 apartment design standards effectively lifted restrictions on the mix of dwelling types in BTR schemes, making it inevitable that most would contain a preponderance of studios and one-bedroom units with little or no private outdoor space such as balconies.

The final piece came in December 2018 when Murphy promulgated his Urban Development and Building Heights guidelines, based on the notion that much taller buildings were needed to increase urban density and reduce suburban sprawl. These required planning authorities to “actively pursue” increased building heights and facilitate high-rise proposals in line with flexible “development management criteria”.

Four years of mania

As I noted in my last book, A Little History of the Future of Dublin (2021), “The combination of dumbed-down apartment design standards, direct applications to An Bord Pleanála for Strategic Housing Development (SHD) schemes and a virtual free-for-all on high-rise development upended the concept of ‘proper planning and sustainable development’ – the ultimate goal that the planning system is meant to achieve.”

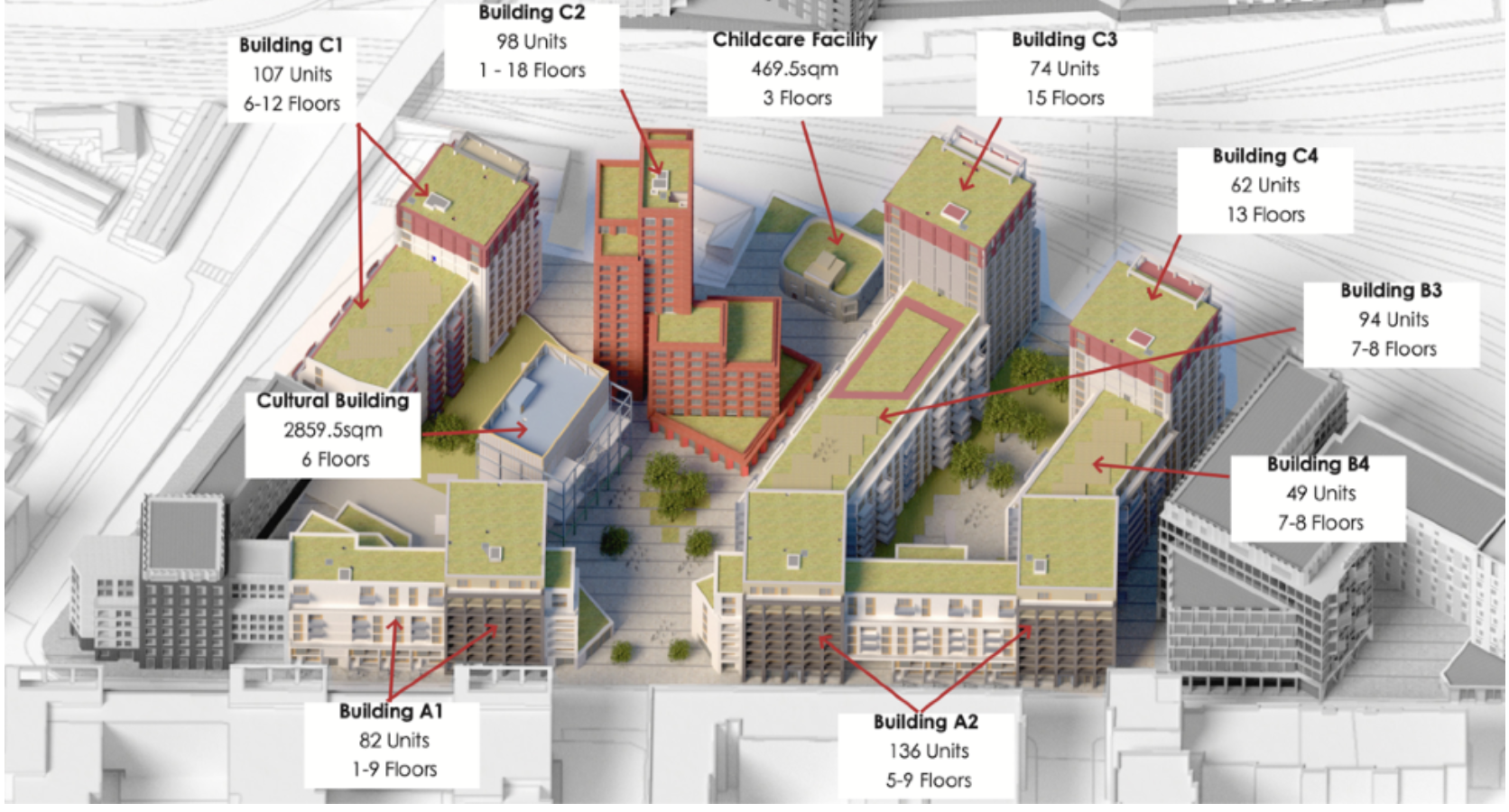

The SHD planning mania that followed was intense, lasting for four years, and left us with random eruptions of high-rise BTR blocks built at extraordinarily high densities. One of the most egregious examples is nearing completion at Eglinton Road in Donnybrook, where six semi-detached houses have been replaced by 148 apartments rising to a height of 12 storeys, with a density equating to 385 units per hectare.

Although Eglinton Place was approved in 2020 as a build-to-sell scheme, the development was sold last February to M&G European Living Property Fund for €99.5 million – an average of €672,300 per unit. Similarly all 342 apartments in Griffith Wood, Marino were snapped up in March 2022 for €176.5 million by US real estate fund Greystar – the smallest one-bedroom units there are renting for €2,140 per month, or €25,680 per year.

What’s really remarkable though is that so many developers didn’t activate their permissions. Detailed statistics* compiled by the Dublin Democratic Planning Alliance from the Building Control Management System show that construction got underway on just 27 percent of 46,867 apartments, 30 percent of 16,040 student bed spaces and 44 percent of 15,291 houses approved by An Bord Pleanála between 2018 and 2022.

This is at least partly due to the hoarding of land for speculative purposes, “with a view to greater resale value”, as a report by the Department of Public Expenditure noted last December. But there is another reason: high-density apartment schemes have become economically unviable due to the steep hike in interest rates and construction price inflation over the past 18 months, as well as the considerable extra costs of building tall.

With the sums no longer stacking up on numerous other high-rise apartment schemes, such as a proposed 30-storey tower opposite Heuston Station, as the wall of money from institutional funds suddenly dematerialised, PII did an abrupt about-turn and began lobbying in mid-2022 for the adoption of a “low-rise, medium-density” model, arguing that this would make housing construction more viable in the current climate.

Desperate for any proposal that might help to address its failing targets for new homes, the Department of Housing published a consultation paper last March on proposed new housing design standards. It not only adopted the latest PII proposal but even used similar language as the lobby group in stating that continued reliance on suburban design standards, dating from 1919, was precluding more “compact” housing models.

Although this model would be a move in the right direction, the department’s paper left the door open to future high-rise construction in Dublin and elsewhere, if – as PII hopes – apartments become viable once again. It does so by specifying densities with regard to units per hectare: up to 300 in central areas of cities; up to 150 in towns within metropolitan regions and other large towns; and up to 80 in suburban areas.

Fianna Fáil housing minister Darragh O’Brien had already put an end to co-living schemes, phased out SHDs and revoked the 2018 apartment design guidelines tailored for BTR schemes, having concluded that these initiatives – taken by his two Fine Gael predecessors – were policy failures. Since then, all applications for large-scale residential developments have been dealt with by local authorities, as they were in the past.

A BTR bailout

Now the government is planning to “invest” up to €8 billion, via the Land Development Agency, in what amounts to a bailout of the BTR sector to activate at least some of the permissions for high-density apartment schemes that are lying idle. In return, developers would have to set aside a proportion of these subsidised schemes for cost-rental homes that would qualify as affordable housing, with the rest being rented out at market rates.

What’s clear is that five years have been wasted on pursuing the wrong policies to deal with a housing crisis that Leo Varadkar described as a “national emergency” in 2018. The government over which he once again presides is only now getting around to resolving its root cause – the acute scarcity of affordable housing, with residential property prices at record levels, stratospheric rents and the number of homeless people rising inexorably.

As TU Dublin’s Dr Lorcan Sirr has said, “There is no great doubt who is really responsible for much housing and planning policy in Ireland, and it is frequently not the minister of the day. The property lobbyists have left their DNA at policy crime scenes with impunity, having little fear of ever being held responsible… Lobbyists will do what lobbyists do. The minister’s job is to act as a bulwark between these industry demands and the needs of society.”

- The figures given are for “ready-to-go” planning permissions and exclude applications withdrawn, refused, quashed or under judicial review.

An Bord Pleanála's Best Laid Plans

An Bord Pleanála’s reputation for impartiality and fair-mindedness was the principal casualty of Simon Coveney turning it into a one-stop shop for strategic housing development (SHD) applications, with trolley-loads of documentation wheeled into the board’s offices on Dublin’s Marlborough Street on behalf of the Planning-Industrial Complex.

The board set up a dedicated four-person division to deal with fast-tracked SHD applications under Coveney’s 2016 legislation, headed by Paul Hyde, an architect who had been a close friend of Coveney since their primary school days in Cork; they later jointly owned a class 1 Dubois 36 sailing yacht named Dark Angel.

In 2018, the Government appointed Dave Walsh, former assistant secretary-general in charge of housing and planning, who had overseen radical changes in planning policy, as chairperson of An Bord Pleanála. Three months later the department’s chief planner Niall Cussen, who had worked closely with Walsh in drafting the new policies and ministerial directives, was appointed as Ireland’s first planning regulator.

By the end of 2021, all of An Bord Pleanála’s eight members had been either appointed or reappointed by former housing minister Eoghan Murphy, and they clearly saw it as their duty, even mission, to implement national planning policies.

Decisions on SHDs were made by triumvirates of the board – usually Hyde and former Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland president Michelle Fagan, along with either Stephen Bohan, formerly an engineer with Roughan O’Donovan, professional planner Terry Prendergast, or former Tipperary county manager Terry Ó Niadh. Many of these cases involved high-rise schemes that contravened democratically adopted development plans and generated widespread opposition.

Dozens of aggrieved objectors challenged An Bord Pleanála’s decisions by seeking judicial reviews in the High Court, as there was no other forum for appeal, and this resulted in the board having to spend almost €10 million on legal services in 2022 alone – more than 70 per cent of its operating costs for the year. In the vast majority of cases, its decisions were quashed – mostly for substantial rather than technical reasons.

This caused outrage in the development sector. Demands were made for government to “grab the judicial review issue by the scruff of the neck”, as planning consultant Tom Phillips put it. And that’s exactly what it is now seeking to do in the dystopian draft Planning and Development Bill currently before the Oireachtas, which would severely restrict public right of access to the High Court in planning cases.

The spike in judicial reviews was precipitated by An Bord Pleanála rubber-stamping one outrageous SHD scheme after another. As the Dublin Democratic Planning Alliance noted, many of these permissions were “beyond belief”, grounded on ministerial directives that were “inherently undemocratic” and had “essentially privatised and deregulated the planning system, to the detriment of the fabric of our places and our society”.

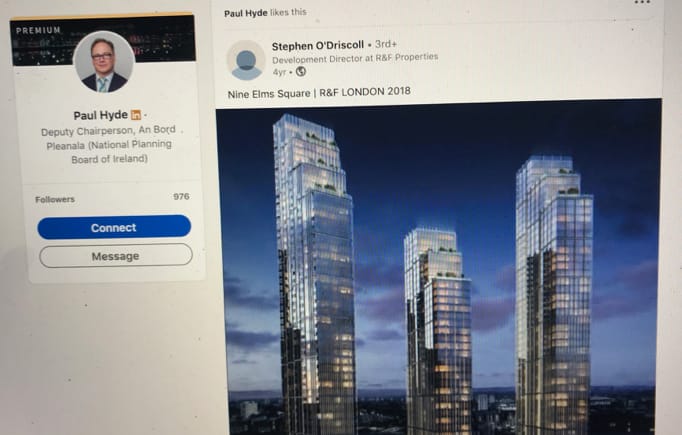

Paul Hyde was right at the heart of all of this. In addition to being the helmsman for SHD applications, he picked the planning appeal cases that he wanted to handle, put pressure on planning inspectors to change their reports, had a romantic relationship with at least one of the inspectors and convened numerous two-member boards – consisting of himself and Michelle Fagan – to make decisions on dozens of planning appeals.

Hyde had a LinkedIn account, identifying himself as “Deputy Chairperson, An Bord Pleanála (National Planning Board of Ireland)”. In 2018 when Johnny Ronan was hatching his audacious Waterfront South Central scheme of two super-tall residential towers for North Wall Quay, Hyde openly advertised his predilection for high-rise buildings by liking a post showing a trio of 36 to 54-storey towers planned for Nine Elms in London.

This clearly contravened the board’s code of conduct, which was adopted in 1996. It states, “A Board member or employee shall not publish or publicly express personal views or opinions which could reasonably be interpreted as compromising his/her ability to carry out his/her official duties with the Board in an impartial manner or as compromising the Board in carrying out its functions in an impartial and objective manner.”

An Bord Pleanála was thrown into turmoil following a torrent of revelations by The Ditch about conflicts of interest involving Hyde and others as well as its dubious pattern of decision making. Hyde resigned in July 2022 and was later charged with nine counts of failing to file proper declarations of interest. After pleading guilty to two of these charges, he got a suspended two-month jail sentence and was fined €6,000. Board chair Dave Walsh took early retirement In November 2022.

The board was left struggling with an unprecedented backlog of 2,300 cases – equivalent to a whole year’s workload – including nearly 60 per cent of all the SHD applications submitted in 2022. An interim chairperson, lawyer and civil servant Oonagh Buckley (who took pot-shots at the legal profession), was appointed by housing minister Darragh O’Brien, who also drafted in 11 temporary board members to expedite decision-making.

An internal board audit by three senior staff officers in October 2022 concluded that there may have been “a concerted attempt to shift certain cultural norms in An Bord Pleanála away from those which have been in place, monitored and guarded by multiple past and present Board members and staff, upon whose efforts the reputation and good standing of the organisation has been built and maintained over 45 years of operation”.

Frank McDonald is the former environment editor of the Irish Times, and the author of several books, including A Little History of the Future of Dublin (2021), The Destruction of Dublin (1985), Saving the City (1989), and The Construction of Dublin (2000).